The mealy-mouthed mothers of injustice

How corporate codes and lawyers' ethics can interact. An example...

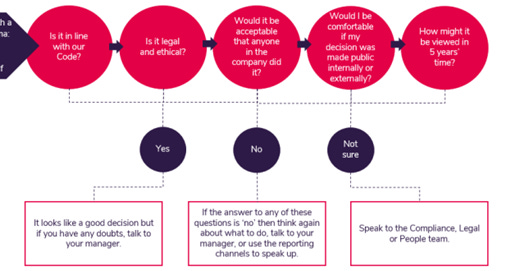

The Post Office Code of Conduct (version 11, November 2023) attracted a bit of Twitter ire recently. I’m not going to get too excited about a corporate code of conduct. Such codes are not generally that effective. Fine words, even when reviewed by the IBE, don’t really butter my parsnips or anyone else’s. I would not go as far as saying they are mere PR, but what happens on the ground counts far more including how the code itself is operationalised. Culture eats conduct and codes for lunch.

It is worth, however, taking a moment to ponder how lawyers contribute to that culture.

Let’s do so by talking a little bit about how an example from the Post Office scandal would fare against these five tests. I don’t know if this code or anything like it was in place at the time, but let’s assume, as a thought experiment, that it was. Let’s take the example of the Post Office’s bullying of sub-postmasters into guilty pleas for false accounting. One way this was done was by charging them with theft when it should not have been done (and sometimes when there was no evidence at all of it).

The Code, of course, has a section on preventing bullying and harassment, so one could argue “no” at the first hurdle: such behaviour is not in line with the code. And if we jump to the last question, how it might be viewed in five years time, the answer is a resounding “no” with a litany of cuss words attached. One might say no, similar to the levels of comfort about decisions being made public internally or externally question, particularly if any of the recent apologies and cross-examinations are held in mind. And the central middle question whether it was acceptable that anyone in the company did it, “no” to.

But people did do it, and the reasons why they did it and continued to justify it to bear examination.

On one level, initially, the answer may simply be they didn’t think about any of these five questions. To put it mildly, culture and competence within the organisation was suboptimal. But when they came to defend it subsequently, they would have thought at least a little bit more carefully: and it turns out they relied heavily on lawyers in so doing. I know, I’m imagining your surprise.

After the Post Office cases blew up in 2013, with the discovery of unreliable “expert” evidence, the post offices favour a prosecution firm Cartwright King conducted a review (including their own cases, classy), bolstered by Brian Altman KC’s General Review and various other advices by him. I have written in outline about those here and in longer form here.

One of those advices focuses on the bullying through overcharging allegation.

Cartwright King had sought to rebut it by saying that false accounting was not less serious to theft, "because they were both offences of dishonesty and both carried the same maximum sentence.”

My basic response, only mildly unfair, to this is: balderdash. But I digress.

As Counsel to the Inquiry (Jason Beer) described it in his opening submission to the Inquiry, on 8 March 2015, Altman gave “important advice” on this point because Second Sight, forensic accountants independently investigating complaints about Horizon and the prosecution of offences under it, were "beginning to advance arguments that [the Post Office] is abusing its prosecutorial role by charging sub-postmasters with theft, when there is no evidence of it, in order only to pressure sub-postmasters into pleading guilty to false accounting".

Counsel to the inquiry says:

“The advice from Mr Altman was sought to ensure that the statement made to Second Sight to the contrary by the Post Office was "defensible". It’s worth pausing a minute there to marvel at such a step being taken.

Mr Altman's …says: "If I may say so, the so-called 'equality' of the offences is an unnecessary and unprofitable focal point of attention. The other issues raised by the letter have greater force and are defensible."

“His conclusions at page 7 were as follows: First, both offences of theft and false accounting do involve dishonesty and do carry a maximum sentence of 7 years' imprisonment. The only argument that may be advanced to defend the statement is that it is accurate 'within the narrow context within which it was stated'. Third, the point was that false accounting may be a lesser offence and may often be a lesser offence in the context in which it is charged, so to argue that it is not a lesser offence is not accurate; it all depends on the circumstances of the individual case. Fourth, the statement was undermined by the fact that the seriousness or otherwise of any offence of theft or false accounting must always depend on its own facts, as is demonstrated by the many ways in which such offences may be committed and how offenders may be sentenced for them.

What Mr Altman is engaged in here is a rearguard, setting out what is defensible rather than what is right. As Counsel to the Inquiry puts it:

“What does not appear is a blunt and unequivocal statement to the effect that, where both theft and false accounting are charged for the same conduct, the charges of false accounting may be seen as less serious, which appears to be exactly the point that Second Sight and Sir Anthony Hooper were both identifying. Also not addressed is whether, in practice, an innocent person may be more likely to plead to what may be perceived as a less serious charge and whether barristers and solicitors are likely to advise their clients that false accounting is, in practice, less likely to result in a prison sentence.”

One interpretation of this submission by counsel is that he is saying Mr Altman’s advice was properly not wrong, at least not definitively, but it was cynical. Through mealymouthed words a significant injustice was drawn out many more years. An interesting question for anyone who actually does care about corporate codes of conduct is that the ‘is it legal’ test may have been passed for the purposes of the Code through this very deliberate putting on of rose-tinted spectacles.